Written by Vosot Ikeida

A Utopia For Mice

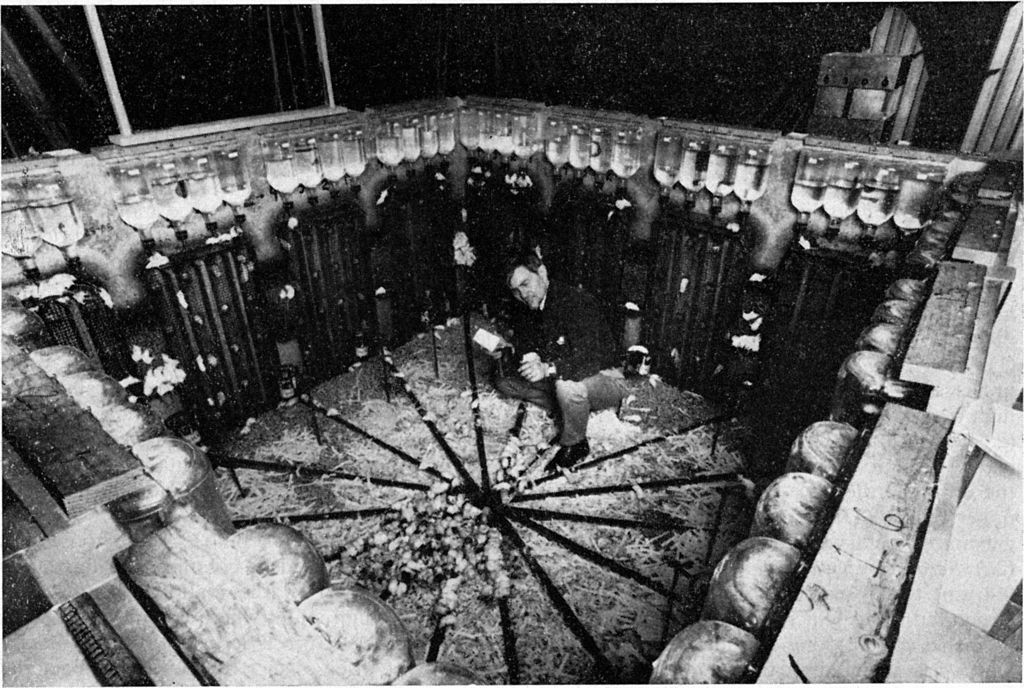

John B. Calhoun (1917 - 1995), an American ethologist, released 8 male and female lab mice into each of the 4 living rooms of a breeding box.

Those living rooms were connected by a bridge, and creating a kind of "society" for the mice, divided into 4 spaces.

Since the optimal number of mice in the box was 48 and the number that was actually released was 32 (4x8), this "society" was a relaxed environment for the them to grow up.

Moreover, food and water were constantly replenished, so they could consume as much as they wanted at any time. In other words, Calhoun had set up a utopia for mice that could not be more favorable.

Calhoun observed how the behavior of the mice changed over a period of 16 months in their small society.

The Mice Begin to Fight

In every box, the mice began to multiply, and doubled in number in 12 months to 80 adult mice.

If they kept increasing, it would be an overcrowded living environment for them. So, newborn babies were taken out of the box and they were eliminated from the society, when the number reached 80.

You might imagine that the mice lived peacefully in this ideal environment, but this was not the case. First, the adult male mice started fighting each other.

It was a power struggle to decide who would be the boss.

Not only the first generation of mice that were released, but also the second and third generation offspring born from them joined the struggle when they were 6 months old.

Before long, more than half of them left the struggle, and a hierarchy was established among the male mice.

As a result, the 4 rooms varied from a comfortable "family room" with a relatively small population density ruled by the powerful "boss" mouse to a dense "square room" where many mice came along.

Among the female mice, two groups were formed up : One was the "householding females" who were kept around by the male bosses of the "family room", and the other was the "square females" who were drifters.

The householding female became a good mother.

When they became pregnant, they eagerly began to prepare for the birth, raking up the pieces of paper scattered around the living room and working tirelessly to build a nest. Even after the birth, they looked after the pups well.

Thus, the mortality rate of the offspring born in the "family room" was only 50%.

On the other hand, the "square females" were targeted for sex by the drifter males.

The pregnancy rate was the same as that of the "householding females," but the square females did not perform well in maternal behavior. Nest building did not proceed well, and some females did not nest at all, and when they gave birth, they occasionally dropped their babies in the sawdust at the bottom of the breeding box.

Even after giving birth, they were not good at taking care of their children and often dropped them when carrying them. The dropped babies would either die or be eaten by other adult mice.

Consequently, the mortality rate of baby mice in the "Square Room" was 96%.

The Birth of "Hikikomori"?

In this way, Calhoun could measure behavioral abnormality in female mice by the mortality rate of their offspring, but it was difficult to find a precise index of abnormality in male mice.

Male mice were divided into five types: A, B, C, D, and E.

A and B are the dominant mice, and their behaviors are closest to those of the so-called normal mice.

Among them, A is a male mouse who became the boss of the room after his own struggle. He could be said to be the lord of the house.

A was not necessarily a belligerent character. Rather, he rarely attacked by himself, and in many cases, he was able to hold the castle because he was always on the defensive.

B was a male rodent who could not achieve the status of the lord of the house, and stayed as a chief warrior in the field.

Compared to A, B's position was unstable and he was often replaced by other male mice in a fight.

C was a love-starved male rodent. Whether the partner was a male, a female, or even a baby mouse, he would immediately initiate courtship behavior. However, their activity was moderate. Even when attacked by the dominant males like A or B, they rarely take the fight to them. They might be a poet-type male rodent that flirts with others.

D was a strange male mouse that Calhoun had named "prober". They did not fight, and although they were weakling, they were very active. They tried to court regardless of who the partner was with. Unlike C, however, D was relentless.

In search of a female, D would peek inside the family room dominated by A. A would stare at him, and then D left soon, but he would not be discouraged and would try the same action again and again.

And, Type E male mice were "hikikomori".

Since they did not participate in fighting, they were not injured and did not lose their hair. Shiny and glossy. E looked healthiest from the outside.

However, the reason why E did not fight was not because of its pacifist beliefs, but rather because of its asocial nature that did not want to associate with other mice.

He stayed holed up in his nest and seldom came out.

He never came out to the common space to eat with other mice.

Moreover, E ate, drank water, and moved around only while other mice were sleeping.

E did not respond to other mice when they see him.

E did not show any interest in females.

E were ignored by other mice and were isolated in the mice society.

Applied to Human Behavior?

Calhoun named the changes in the behavior of the mice observed in these experiments "Behavioral Sink".

Calhoun repeated the same kind of experiments for many years under different conditions, including the type and number of rodents and the size of the cages.

Among them, the most famous experiment called "Universe 25," showed that the mouse population peaked at 2,200 and then began to exhibit a variety of abnormal and destructive behaviors, becoming endangered by the 600th day.

The Calhoun's experiments were mentioned in many science fiction books in the 1970s as a prediction of the future of mankind, which is enjoying the prosperity of a civilization that can no longer starve, unlike in prehistoric times when it was difficult to secure food.

I don't know how much the results of his experiments with mice will help us explain human behavior, but it may show the possibility that behaviors such as "hikikomori" in human society are not just a product of modern society or capitalism, but have existed since the beginning of humanity, beyond history.

(End)

・・・To the Japanese version of this article

・・・To the French version of this article

Reference Site (viewed on January 7, 2021)

This article is not an academic paper, so priority was given to readability rather than accuracy. If you are looking for accurate data, please visit the following sites.

-

Wikipedia(English)John B. Calhoun

-

Wikipedia(English)Behavioral Sink

-

The page introducing "Universe 25" automatically translated into Japanese.

https://ichi.pro/jinrui-no-zetsumetsu-o-yosokushita-osoroshii-kenkyu-39924430866555

-

”Love thy neighbor in City" (Japanese)

https://www.tohoku-gakuin.ac.jp/research/journal/bk2011/pdf/bk2011no02_05.pdf

◆◇◆ Profile ◇◆◇

Vosot Ikeida A hikikomori in Japan, living in Tokyo. Born in 1962. Started hikikomori in 1985, since then staying hikikomori on and off with changing its style. Founded GHO (Global Hikikomori Organisation) in 2017.