Written by Vosot Ikeida

The increase in the Population of Hikikomori

They say hikikomori is increasing.

The word "increasing" implies "there are more hikikomori now than there were in the past.".

However, not only have there been no surveys on hikikomori in the past to compare with but also the term "hikikomori" in the sense we use today did not even exist before 1989, so we can't talk about it. At best, each of us can compare it subjectively only by recalling one's memory in the past.

When I go back to my childhood memories of the 1960s or 70s, I recall those who would be named 'hikikomori' if they live nowadays, were found here and there. Therefore, I don't think the number of hikikomori is 'increasing'.

In recent years, however, more and more local authorities, both in Japan and abroad, have been conducting surveys on hikikomori, and I have been hearing so many announcements and reports on hikikomori. This may give people the impression that the number of hikikomori is increasing.

We must not make that mistake. That was the point I wrote in an article in 2019 as follows.

However, at least we could say,

'In recent years, the number of people identified as hikikomori has been increasing.'

The Decrease in the Population of Children

On the other hand, seemingly unrelated to hikikomori, the declining birthrate in Japanese society are becoming a crucial social issue.

The marriage and fertility rates are declining, and the Japanese society is approaching childless.

Many people believe that this is due to poor Japanese politics and the low birth rate is a characteristic of Japanese society.

However, if you look around the world, the birth rate has been declining all over, not only in Japan but in other developed countries in general.

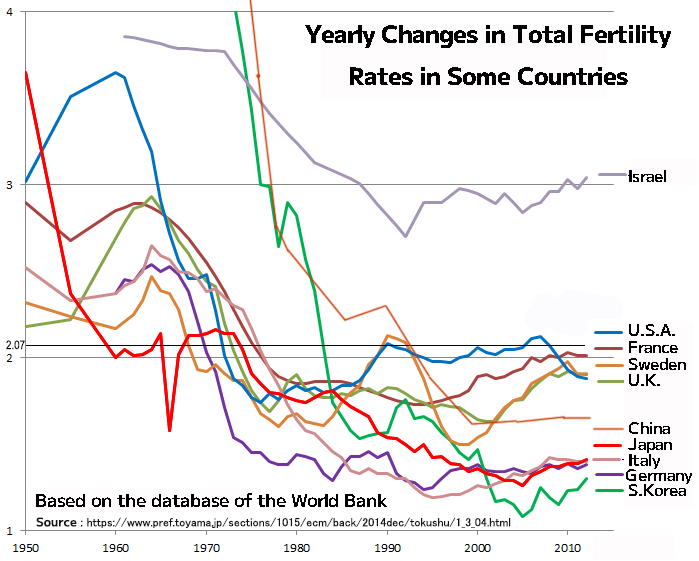

The graph above shows the yearly changes in total fertility rates (*1) for some advanced countries. Although there have been some ups and downs, fertility rates in developed countries have generally declined since the 1950s.

*1. Total Fertility Rate : 'The number that indicates how many children a woman gives birth to on average during her lifetime.' This is the most important indicator to consider regarding the issue of declining fertility. In Japan, when this figure is 2.07, this is called the population replacement level, which means that the population neither increases nor decreases.

Although it was not possible to include it in this graph, the latest information is that on 22 February 2023, it was announced that the total fertility rate in South Korea in 2022 was 0.78, the lowest value in OECD history.

Finally Even China Reverses Policy

As the population grows, more food is needed. China was troubled by population growth until the 1970s. The figures were too large to be included in the graph above, but in 1965 China's total fertility rate was 6.08.

In 1979, China adopted the famous One-Child Policy (一孩政策), whereby a couple could have no more than one child and heavy fines were imposed on the couples who have a second child.

However, the one-child policy has been phased out in recent years as the population of young people has declined in the country: in 2015, a couple was allowed to have up to two children, and in 2021, up to three.

Despite this, the number of new children finally fell below 10 million in 2022, and China's population began to decline for the first time in 61 years.

What, then, is the problem of hikikomori in China?

Various fragments of information have indirectly been transmitted to us that many children who have been over-interfered with by their parents due to the One-Child Policy adopted for a long time are already living in a state of hikikomori as adults.

However, I have not reached the point to hear that the Chinese words that are supposed to correspond to 'hikikomori', such as 'Buchumen'(不出門) or 'Jianjuzu' (繭居族), have become a social problem.

Instead, I often hear that the increasing number of 'Tang Ping'(躺平), meaning 'lying-down young people' who do not consume, do not marry, and do not have children, is often mentioned in the media.

I also hear of the existence of 'Pho Si Nang Zhou' (仏系男子); a man who has no desire for anything, 'Shen Nang'; a redundant man who cannot get any marriage partner, or 'Kong Chao Chin Nyen' (空巣青年); a youth who always deals only with mobile phone and cannot with others, all of which sound like to be similar to the 'broader category of hikikomori' as the Japanese government says.

The Cause of the Declining Birthrate is Economy?

On 30 January, Japanese Prime Minister Kishida announced that he would launch a 'countermeasures against the declining birthrate in a different dimension'.

The substance of these measures is not yet informed when I am writing this line. I predict that the measures will probably consist of economic support for the child-rearing generation.

I am not opposed to economic support for young people, but I cannot agree with the idea that this will stop the trend of declining birthrates.

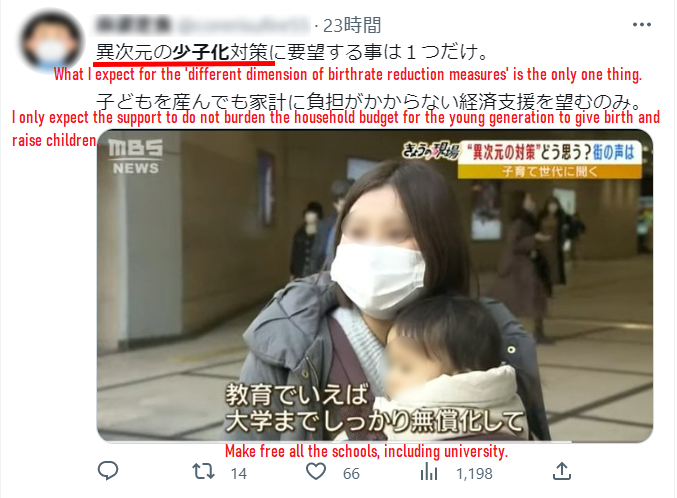

The political argument of the masses usually boils down to 'give us money', no matter what the topic. The declining birthrate is no exception, with tweets and reports such as.

I am not against free education, but if it was to be implemented, given the realistic Japanese character, most parents might think this way.

'If it's the same free-of-charge, I want my children to enter a better university.'

They will probably spend the money they used to pay for university on the educational industry, such as preparatory or cram schools. Consequently they will only put pressure on household finances. The similar case actually occured in South Korea before.

In any case, I don't think that free education is a fundamental solution to halt the declining birthrate.

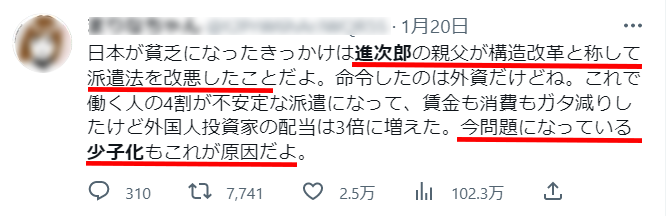

Also, such a tweet has been exploded with as many as 25,000 supporters.

It means, "The declining birthrate in Japan is due to neo-liberalism that started from the Koizumi Reform since 2001."

Is that really so?

If we could manage the phenomenon of declining birthrate by distributing money to the child-rearing generation, all the poor developing countries that cannot do so should be worried by now. Also in the 1980s, when Japan was much richer, there should have been no signs of declining birthrate in this country.

However, all the facts show the opposition.

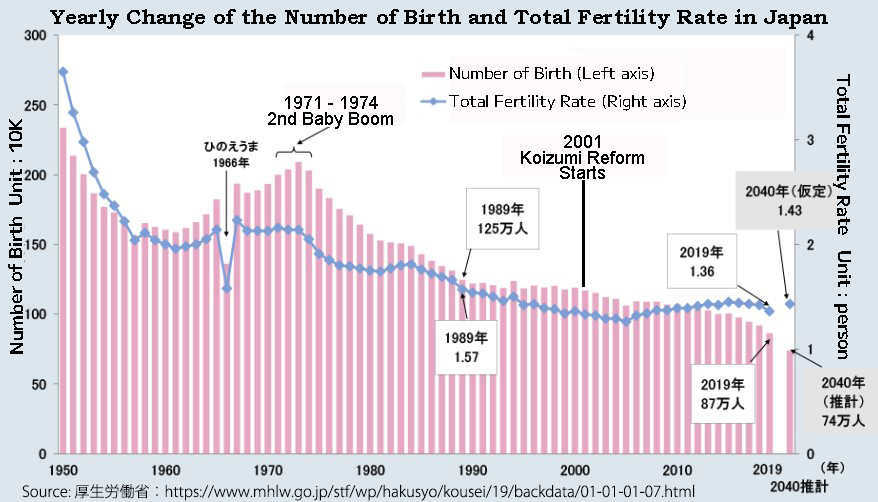

The decrease in the total fertility rate has begun in 1947 in Japan, a long time before the bubble economy era in the 1980s, and needless to say, it was much before the Koizumi Reform in 2001, as shown in the figure below.

(Based on the resource by Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan with my addition)

Moreover, the analysis of the Gini coefficient; the standard measure of income inequality, shows no evidence that the Koizumi Reforms in the early 2000s increased inequality in Japan.(*2)

*2. "Is is true the Japan's inequality was expanded during the Koizumi Reforms?" (岸田発言で注目:小泉政権時代に、日本の所得格差が広がったのは本当か?) by SATOH Ayano(Takasaki City University of Economics)SAKISIRU 2021.10.22 https://sakisiru.jp/12905

So what about it internationally?

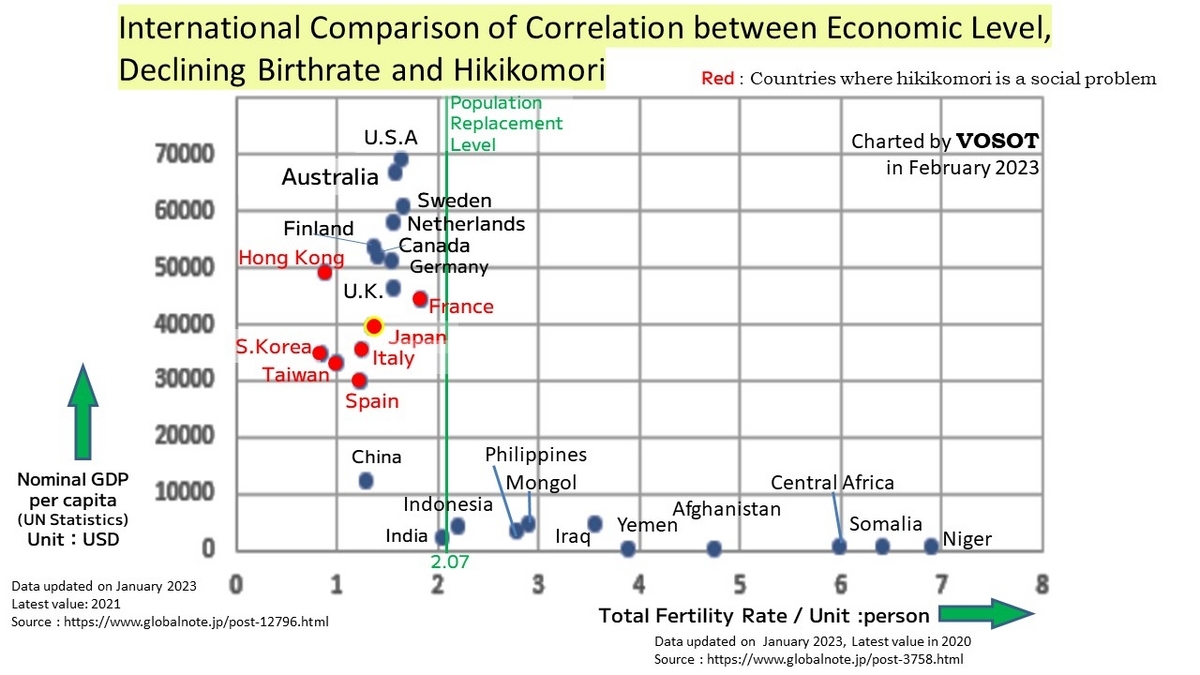

As the chart below shows, it is not the poorer countries that have a declining birth rate, but rather the economically richer ones.

Economic Level, Declining Birthrate, and Hikikomori

Economically poorer countries generally have higher total fertility rates, so the fertility decline is not a national or social problem there. Behind this, there may be other social problems like poor public health conditions and high infant mortality rates.

In any case, we cannot find any evidence to support the policy that "distributing money to the child-rearing generation will fundamentally solve the problem of declining birth rates".

However, everyone wants money.

Then, there will always be intellectuals who inflame the masses and try to justify their desire to "give me money" by using socially-hot problems that are happening right in front of them as a subject.

Intellectuals who advocate convenient theories for political power are disgracefully called 'imperial scholars', but the ones who abandon academic objectivity and neutrality, flatter the masses, and twist plausible theories are just as guilty and shameful as imperial scholars.

In Japan, many intellectuals have unduly theorized about the declining birthrate to satisfy public give-me-money needs as such.

The Legends of France and Sweden

If I say,

"Look at the world, and you will see that the fundamental solution to fertility decline is not distributing money to the child-rearing generation",

then some people may immediately retort:

"No. Look at France and Sweden. They have developed countries with low fertility rates, but their fertility rates improved because they adopted policies to support their child-rearing generations economically."

France and Sweden are legendary for their success in combating falling birthrates.

But what happened there really?

First of all, France and Sweden did not only provide financial support to the child-rearing generation but also mainly revised civil law relating to family structure.

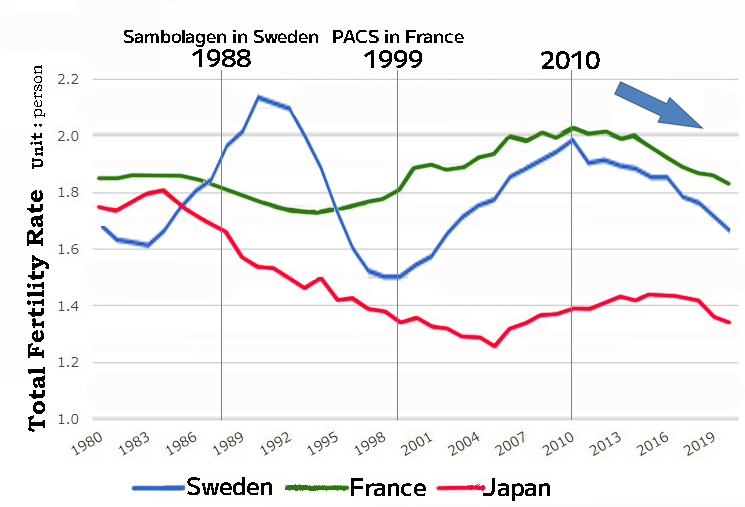

In France, the birth rate was 1.65 in 1994, the lowest in their history, and the Chirac Government, feeling a sense of crisis, introduced PACS in 1999. This led to a large number of children born out of wedlock to unmarried couples, and the total fertility rate recovered to 2.01 in 2010.

In Sweden, Sambolagen was already in force in 1988. This led to a two-year surge in the fertility rate, which peaked at 2.13 in 1990 and then began to decline again, falling to 1.50 in 1999, the lowest in their history. It then continued to rise again until 2010.

We should know well that total fertility rates in France and Sweden began to decline again after 2010.

In other words, the French and Swedish successes, as described by some Japanese "specialists", were only temporary, the effect disappered after a certain period, and the birth rate returned to a downward trend.

I have drawn a graph to illustrate these changes between 1980 and 2020, as below.

What does this fact tell us?

I think it tells that even the idealised measures taken by France and Sweden to combat the declining birthrate are symptomatic treatments that can only work very temporarily, and they do not provide a fundamental solution to the major trends of civilisation.

If the Kishida cabinet in Japan is to provide economic support to the child-rearing generation as the 'countermeasures against the declining birthrate in a different dimension', he will have to take these historical facts into account beforehand to prevent further increases in deficit financing.

What, then, are the deeper causes in the civilisation for the declining birthrate?

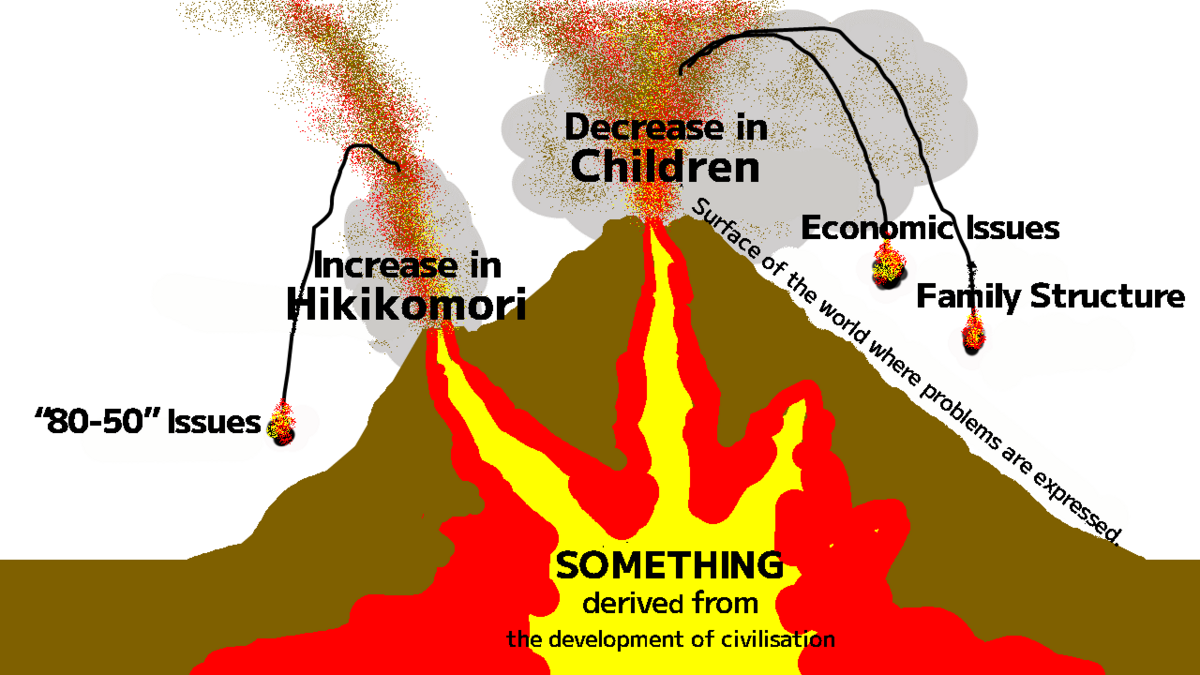

Common Causes of Hikikomori and Low Fertility.

Hikikomori is usually not working. We are also likely to be not married and have no children.

As working in a factory is a comprehensive example, working is production. Having children is the reproduction of the population. In any case, we could say that hikikomori is the people who stay inside not to get involved in "production".

I have been a hikikomori for more than 35 years, which means I have lived a life that has never ventured into economic or demographic production.

I cannot help feeling that what has kept me inside from getting into economic production and what did me so from having and raising children are the same things that derived from the deep side of the evolution of civilization.

In this article, I have looked over the issues of hikikomori and the declining birth rate from a macro perspective. However, in the next article, I will consider it from a micro perspective based on my personal feelings.

・・・Continued to Part II

......To the original Japanese version